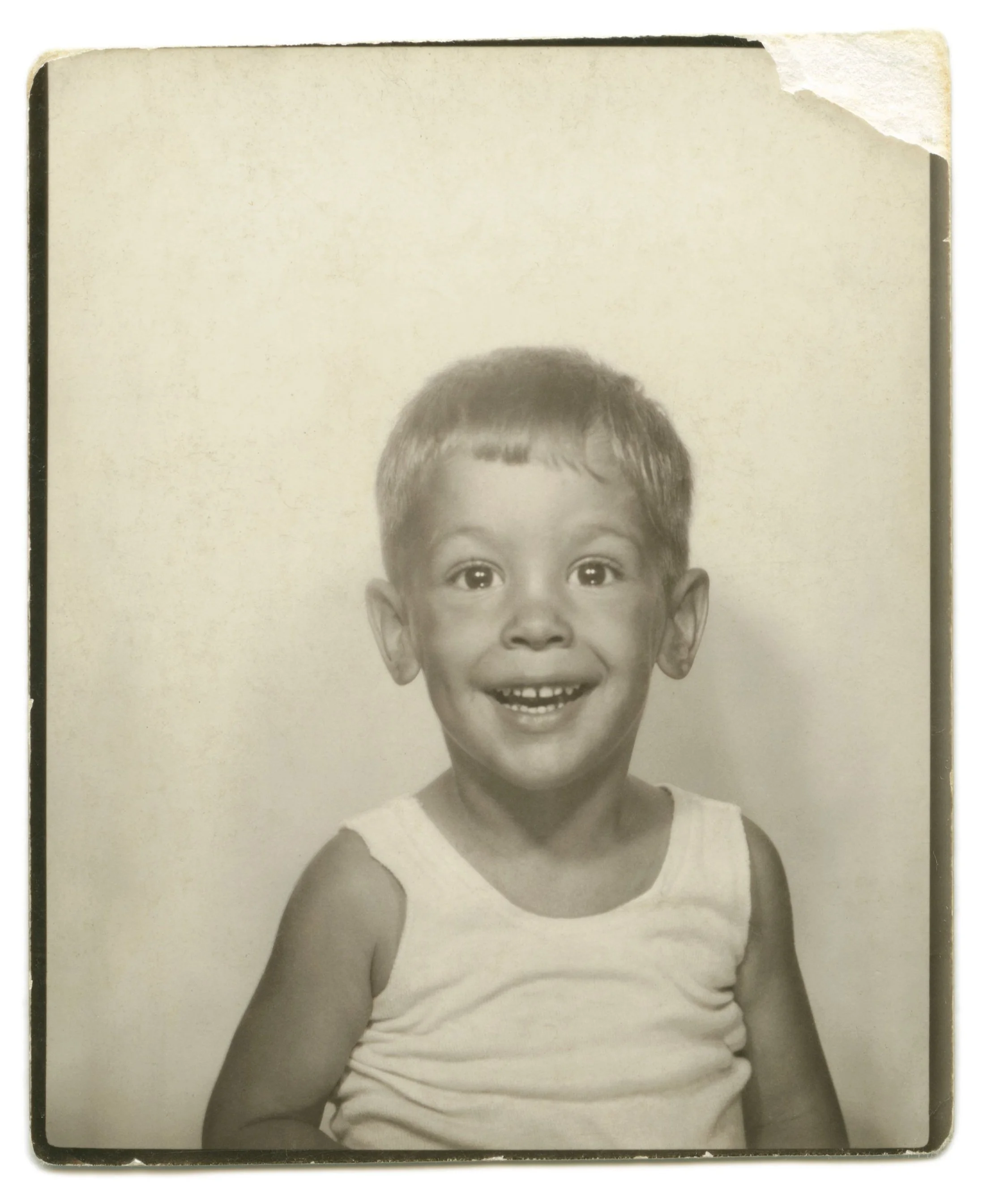

Between the time my original photobooth image was taken until the week my family moved from the Bronx, something unforeseen and unwelcome had taken hold of the neighborhood. In its early stages, my childhood was of a standard format for a boy: little responsibility, childish horseplay, daring, secretive escapades that any responsible parent wouldn’t approve of, occasional jaunts to Orchard Beach, a sad shoreline on the skirts of a swamp, snoring trips to our grandparents, sometimes dressed to the nines, bingeing on Soupy Sales and Chuck McCann, mustard sandwiches, Chiller Theater, Winkie Dink, an endless diet of penny candies and saccharin, Gabila knishes and bottles of YooHoo, gumming up and scratching my older brother’s pristine record collection, stealing money from my mother’s pocketbook to go to White Castle’s, trying on the latest curse words culled from the public school yard, and the nursing of numerous skinned knees or open wounds, cat clawings and dog bites, proving that a budding immune system does a damn good job. The family was a mixed lot of circumstances. As building superintendents, my Irish grandmother cleaned apartments, at times hauling heavy ashcans out onto the sidewalk, and my German grandfather, who read TV Guides with a magnifying glass in-between gulps of beer and baseball innings, occasionally fed coal into a massive, glowing furnace below their apartment, as though he was powering the Titanic. My mother, until a certain year, performed the duty of housewife and maid to her children, none of whom would dare lift a finger to help. My Italian grandmother, a seamstress and the more humorless of the bunch, lived alone, her husband having abandoned her to start a new family elsewhere. All the while, my father trekked twenty miles to an office at the tip of Manhattan each weekday, driving cabs on his days off. And for just a little bit of cash. Yet, in its messiest form, it felt sane and consistent. I was generally happy in my first few years, yet, there were a few

interesting challenges. We lived at the lower reach of the Bronx, in a development called Soundview Projects (now referred to as “Soundview Houses,” a flaccid attempt to make it sound more attractive). It was a simple scheme; a cluster of like-structures mainly reserved for lower to mid-income families. These developments of varying heights were ushered in by the likes of Robert Moses and the MacNeill Mitchell/Alfred Lama Building Authority to shelter newer, post-war families during the 50s. According to my father, the intent to these complexes was for families just starting out, eventually allowing them to move into bigger and better housing being planned for later. That would never come to pass. It became more of an unintended social experiment, to see how humans could function within a petri dish, with little room for escape. By the mid-60s, it must have seemed obvious to our parents that they were somewhat duped, providing them the delight of seeing the neighborhood’s undoing, the influx of an escalating heroin market, racist street gangs like the Black Spades and The Savage Nomads terrorizing anything on two feet, shootings in the hallways, bodies at the end of the street, pedophiles lurking just below our apartment, arson and theft as common as blinking (you didn’t dare own anything new unless you “jacked” it up beforehand to make it “un-stealable,” including your sneakers. I’d lost a bicycle for not doing so). In that current social climate, we were caught in a war of someone else’s making. It was inevitable that I’d be punched and kicked by two sons of one of Malcolm X’s killers, simply to teach me the absurd lesson: Your Honkey White ass is not welcome here! (Ironically, I lived there long before they did). What a delicate message for a six year old, my principal concern being nothing more than calculating

the number of gum balls I could fit in my mouth until my jaw ached. These were someone else’s issues but I had to deal with the collateral, nonetheless. As the mood edged downward, “White Flight” to places like CoOp City, another Mitchell/Lama enterprise at the other end of the Bronx, would signal the death knell to the calm in the area. While my siblings (and parents) dealt with the rapid changes in their own way, some better than others, I would eventually shelter indoors as much as possible. I was never sure who to trust any longer, especially when asked for money. I became a loner. My friends were mostly relegated to the school. My altar boy training was less about being closer to God or brown-nosing my teachers, than being hidden in a quiet and peaceful place for a time. It had its human moments, too, like free swigs of church wine when no one was looking. The priests, in brown floor-length robes, belted ropes and Jesus sandals gave the impression they were caring and noble attendants and one might feel protected in their midst. Until, of course, one puts his hand down your pants. That seemed to be the prevailing dichotomy: All things are fine and good until they aren’t. Important lessons were everywhere. Watching who’s walking behind you was the norm. I learned never to carry money in my pockets but in my socks, never to fall to the ground while being beaten, never to wear a backpack by both straps (it’s better to lose the bag to someone than be flung to the ground by it), Klick-Klacks were never truly a toy (their real use was as weapon), never take the back stairway into the building unless you were fleeing someone, never ride the elevated trains unless in a pack, never accompany an adult stranger to the candy store, never sit at the back of the bus or you risk losing your schoolbooks, never try to act like

a tough guy when there’s a gun aimed at your face, never eat an entire box of Redhots in one sitting, and never, ever, agree to Sleep-Away camp. The trick was to not make yourself the target, essentially sneaking around your own neighborhood. It meant getting indoors by the time the street lights came on. The neighborhood’s charms didn’t end there. In and around 1970, a person could delight in the warm glow of tenements burning to the ground in the abutting neighborhood of Hunt’s Point, some of the structures set afire by their own tenants. When a library was installed nearby by Mayor Herman Badillo, I couldn’t help but think, “Who the hell’s going to use it?” Sadly, most residents in the area, of every ilk, were trapped in the crumble, some to this day. Our parents were correct to send us to the local Catholic school. As much as we may have resented it, there was sanctuary in it for several hours a day, I’m guessing, a small solace for our parents. Not everyone was as lucky. If you’d look at the area now, you’d never know what went on there. It looks tame and feasible. Yet, at one point, Soundview Projects was regarded as one of the most crime-ridden housing projects in the U.S. But, who knew anything else? I imagined that the rest of the country met the same fate. Our textbooks spoke otherwise. The geography lessons we flipped through touted alternate worlds of mostly White kids gorging on worm-less, red apples as they romped on farms or rafted on rivers, like a bunch of Huckleberry Finns, colorful, thoroughly scrubbed images of major industry, leaking only safe chemicals into rural waterways, lines of bed sheets drying

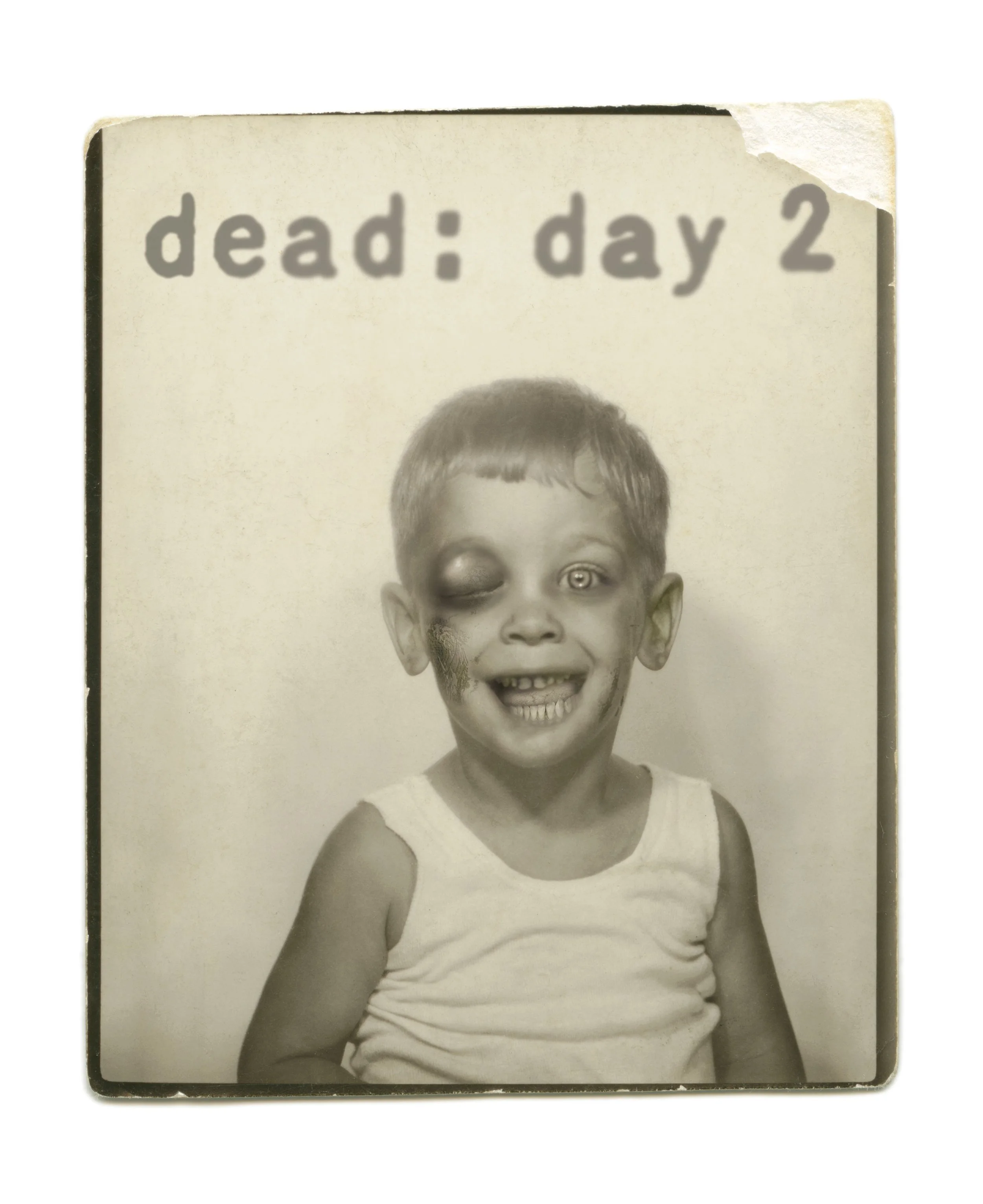

in the immaculate air, upstanding farmhands pitching hay for the father country, under clouds that never rained. I had no idea where any of this pap was or if I’d ever experience it. It was a bromide. Who’d have imagined that one gentle man, a ice cream vendor in a repurposed mail truck, catering to the neighborhood kids with brightly-colored and inexpensive frozen treats or boiled frankfurters on a bun, would end up dented by a bullet to his right forehead? How much money could the man possibly have had on his person to try murdering him for it? It never seem to matter. The world had tilted off its axis and the task of each kid was to look out for himself and carry on. This photo series kind of runs along the idea that what we knew previously was over and lost. It’s better to face things as they are, eroding on the surface while, underneath, lie an unruffled person, hoping this is all temporary. Thankfully, one day, I’d find out it was.